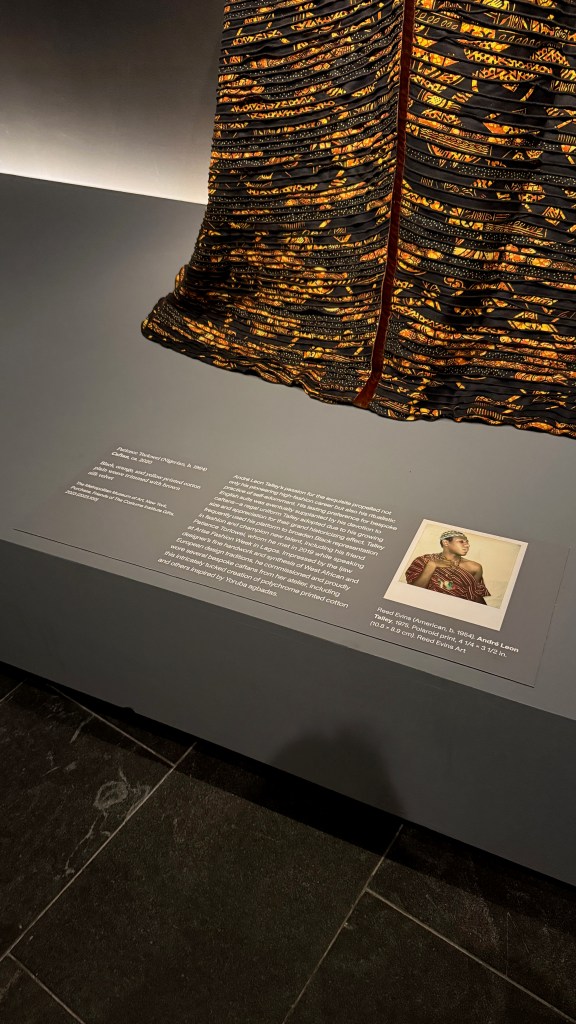

Walking into The Met’s “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” exhibition felt like stepping into a cathedral of couture—one where every garment whispered stories of rebellion, refinement, and revolutionary style. But for me, this wasn’t just any fashion exhibition. This was a pilgrimage to honor André Leon Talley, the towering figure who transformed fashion journalism and redefined what it meant to be a tastemaker in America who sadly passed away in 2022.

I’ve been captivated by André since watching The September Issue in 2009, mesmerized by his theatrical presence and encyclopedic knowledge of fashion history. His memoir The Chiffon Trenches (which I cannot recommend highly enough—seriously, get the audiobook for his magnificent cadence and enunciation) revealed the complex journey of a Black man navigating the predominantly white world of high fashion. André was, quite simply, my reason for making this trip to The Met.

The exhibition itself is a masterclass in how fashion can be both armor and art. From the military-inspired precision of the opening gallery’s ornate jacket—resplendent with gold braiding and ceremonial grandeur—to the rainbow of sequined and satin ensembles that followed, each piece told a story of Black excellence in tailoring and style. The curation brilliantly traced the evolution of Black fashion from historical military uniforms to contemporary couture, showing how clothing became a language of power, pride, and self-expression.

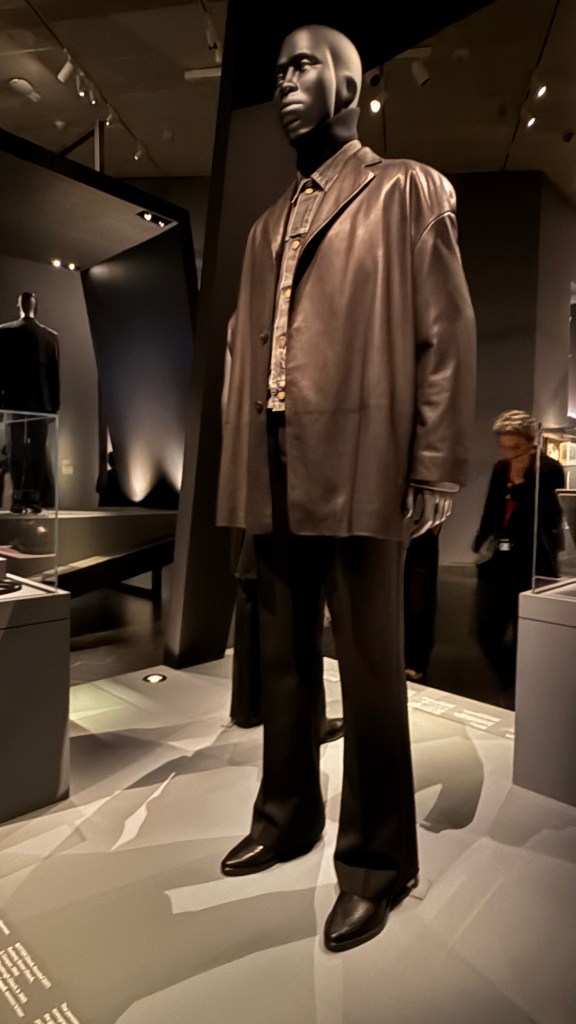

But nothing prepared me for the emotional impact of André’s personal pieces. There, displayed with the reverence reserved for precious artifacts, were his elaborate caftans—those magnificent, flowing statements that became his signature. Standing before them, I could almost hear his voice describing their provenance, their drama, their necessity. These weren’t just garments; they were extensions of his very being, architectural marvels that announced his presence before he even spoke.

Equally captivating were his exquisite Louis Vuitton and Tumi travel cases, arranged like treasures from a grand expedition. These weren’t mere luggage—they were the tools of a global citizen who understood that presentation was everything, that even the act of traveling should be performed with style and intention. The monogrammed cases spoke to André’s understanding that fashion was about more than just clothes; it was about creating a complete aesthetic experience, from the way you packed to the way you presented yourself to the world.

Seeing a vintage Jet magazine cover featuring Walt “Clyde” Frazier in one of his sumptuous fur coats added another layer to the narrative. This legendary New York Knicks point guard was a man who knew how to craft his image, and who used fashion as both shield and sword. The magazine was displayed with one of Clyde’s stylish hats – a perfect pairing.

“Superfine” succeeds not just as a fashion exhibition, but as a meditation on identity, creativity, and the power of personal style. It’s a reminder that clothing can be political, that elegance can be rebellious, and that sometimes the most profound statements are made not with words, but with the cut of a jacket or the sweep of a cape.

André Leon Talley taught us that fashion was never just about clothes—it was about dreams, aspiration, and the audacity to take up space in rooms where you weren’t necessarily welcome. This exhibition is a fitting tribute to his legacy and a celebration of the countless Black designers, tailors, and style mavens who have shaped fashion in ways that are finally being recognized and celebrated.

“Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” is more than an exhibition—it’s a love letter to the transformative power of impeccable style and the individuals brave enough to wear their brilliance on their sleeves.

The exhibit runs through October 26.